It’s hard to explain what it feels like when someone you thought you knew intimately starts to repeat conspiracy theories about the pandemic and vaccines. You don’t really grasp what’s happening immediately: it’s too vast and jarring a realisation to gulp down in one go. So you go through phases. First you clutch at straws. Perhaps it’s a bad joke, or they didn’t really mean it, or they’re just misinformed. Then you enter a stage of hot, disorienting rage and frustrated remonstration. Once that is spent, finally you cool off. But inside you is a leaden realisation that not only is this person you love putting their life at risk: perhaps you never really knew them at all.

People with the wildest theories about the pandemic can be found in countries even where most people don’t have access to the internet, cable TV or the shock jocks of commercial radio. A common impulse is to write off those espousing conspiracies, consigning them to the casualties claimed by WhatsApp groups, disinformation or silent mental health issues. These things may be true – but vaccine hesitancy is a symptom of broader failures. What all people wary of vaccines have in common, from Khartoum to Kansas, is their trust in the state has been eroded. Without understanding this, we will be fated to keep channelling our frustrations towards individuals without grasping why they have lost trust in the first place.

This mistrust can run so deep that people will trust almost any source of information other than the government. In my birthplace of Sudan, fewer than 1% of the population have been fully vaccinated and ventilators are even rarer than vaccines. The story is much the same in several other African countries, where vaccine availability is so poor that people will drop everything and head to a hospital based on nothing but a rumour that free shots are available that day. But for many other people, those rare lifesaving vaccines sound suspiciously like too much of a good thing.

When the first batch of donated vaccines was sent to Sudan earlier this year, two vulnerable members of my family rejected them because someone had started a rumour that an electrical power shortage in the country meant vaccines couldn’t be properly stored, and thus they would certainly have “gone off” and be harmful. I and others tried to convince them that, even if that were the case, the worst case scenario was the shots would be ineffective rather than actually harmful. Our efforts were futile. Still, I clutched at those straws, hoping that once the first shots were administered and no harm was reported, my relatives would come round. But their excuses were ready. The new batch was a “reject”, I was told, donated by western countries that sent the vaccines to Africa for some good PR rather than throwing them away.

This sounds like completely irrational behaviour, but in fact it is the opposite. In countries such as Sudan, nothing good, and certainly nothing free, comes from the state. The government is an extractive body that exists not to serve citizens, but to rifle through their pockets and charge them for going about their daily business. Corruption is endemic – from bribing one’s way through traffic violations, to being forced to use private hospitals because government cronies have hoarded medical technology. The state is something that you thrive in spite of. The government’s communication reflects this uneasy relationship. Officials speak to the public either to scold them or spread propaganda, and dissent is banned; in Egypt, doctors who contradicted the government’s account of the pandemic were arrested, while oxygen tanks ran out in intensive care units in Cairo.

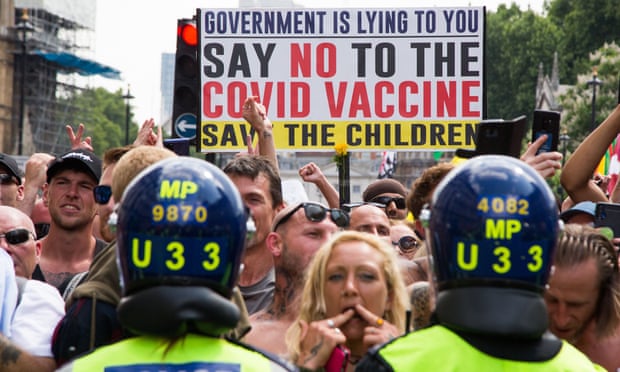

How do you try to convince someone that the provision of free and effective Covid vaccines is the exception to the rules they have lived under their whole life? That vaccines are a sudden outbreak of generosity and competence? Suspicion is easily sown, because political systems don’t need to be fully authoritarian to sustain exploitative and dishonest regimes that breed mistrust. You might think there is a dodgy hidden profit motive behind Covid vaccines if you live in the US, for example, where there is extreme political resistance to publicly funded healthcare, an outrageously profitable healthcare and pharmaceutical industry that spends $306m (£221m) on lobbying a year, and exorbitant, unregulated pricing of everything from flu shots to holding your baby after birth. You might, if you lived in the UK, doubt the government’s assurances that the vaccine had been rigorously tested, after seeing senior officials appear to make up pandemic policies as they went along, dragging the nation with them through U-turns and lockdowns whose rules they did not follow themselves.

State failure breeds paranoia. And when trust in government breaks down, people turn to personal vigilance. This climate of hesitancy and wariness is heightened by poorly regulated media that trade in falsehoods. In the UK, for example, a misleading report about ethnic minority people being excluded from vaccine trials was resolved only with a short correction in a footnote.

Vaccine rejection doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It’s easier to dismiss hesitancy and conspiracies as unhinged behaviour; it makes us feel less unnerved by displays of unreason from those who we think are, or should be, rational people. Sure, among vaccine-hesitant people are those who are simply stubborn, misanthropic or selfish. But, just as the pandemic exploited the weaknesses of our economic and public health systems, vaccine hesitancy has exposed the weaknesses of states’ bond with their citizens. There are no easy answers for how to deal with those who repeat conspiracy theories and falsehoods, but scrutinising the systems that lost their trust is perhaps a good place to start.