Egypt has provided a window into the ancient world. Some of the world’s oldest civilisations have at one point called the North African country home. Snippets of their societies and cultures have been unearthed over the years, often buried deep beneath the soil and sand, preserved by time.

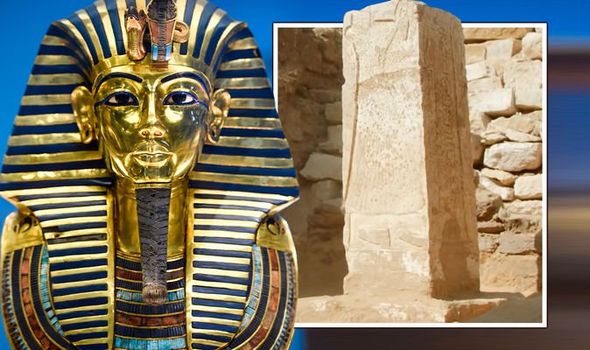

Perhaps the most famous and renowned in the present-day is Tutankhamun, commonly referred to as King Tut, the child king who ascended the throne at the age of eight or nine.

He went on to reign for around nine years, taking over from his father, Amenhotep IV.

Radical reform came under Amenhotep IV’s rule, who changed his name to Akhenaten as he decreed that Egypt would no longer worship multiple gods, but instead focus on the sun god Aten.

The process was known as the Amarna Revolution, and shook Ancient Egypt to its core.

Tarek Tawfik, an archaeologist leading a dig during National Geographic’s, ‘Lost Treasures of Egypt’, exclaimed that excavations are always “exciting” events.

He and his team had found a number of painted walls, and were in the process of moving them from the site to the store rooms for safekeeping, when he spotted something in the sand.

After digging away at the sand, a pillar soon made itself clear.

He said: “And I can see already there is a djed pillar decorated on it.”

The djed is one of the more ancient and commonly found symbols in Ancient Egyptian religion.

A pillar-like symbol, it is meant to represent stability and is associated with the creator god Osiris of the afterlife, the underworld and the dead.

It was an important find, confirming that the nature of Ancient Egyptian religious beliefs in the years after the Amarna Revolution continued to be polytheistic.

Further revealing the pillar from beneath the sand, Mr Tawfik said: “This is exciting, the deceased is appearing now as he would have been carrying the djed pillar.”

Ancient Egyptians painted the djed symbol on the bottom of coffins and wrapped the mummy with djed amulets to summon Osiris and rejuvenate the soul of the deceased.

They also carved djed symbols onto the pillars in their tombs, to follow Osiris to the afterlife.

However, after the Amarna revolution, this belief in Osiris changed.

As Professor Ola El Aguizy, an archaeologist, said: “In the time of Amarna, they told them that there is no afterlife.

“Afterwards, there was an extreme reaction to anyone worshipping Osiris.”

The team found inscriptions to Osiris and Ptah, gods whose worship Tutankhamun’s father had forbidden.

But because the pillar was dated to after Tutankhamun’s death, the narrator noted: “It’s more evidence Tutankhamun had abandoned his father’s revolution.

“He had restored belief in the afterlife and the power of all Egypt’s gods.

“The religious revolution demanding the worship of a single sun god was over.”

Yet, Tutankhamun’s own tomb contained nowhere near the number of djeds or the grandeur that might be expected for one of the great pharaohs.

Aliaa Ismail, an Egyptologist, set out to investigate the mystery during the documentary, attempting to find out why Ay, Tutankhamun’s successor, banished him to such a small and poorly decorated tomb.

Examining Ay’s tomb for clues, she pointed to a wall filled with artwork of baboons, and said: “Both Tut and Ay opted for the same scene, almost like the same person chose what goes in each tomb.”

Both Ay and Tutankhamun’s tombs are uncanny, suggesting that a common hand was at work on both.

Yet, only Ay’s tomb was fit for a pharaoh.

Ms Ismail said: ‘It’s very similar to the tomb of Tutankhamun — the style, the artwork, the sarcophagus.

“But, it’s so much bigger.”

The narrator noted: “The artistic style of the two tombs suggests that Ay may have been responsible for decorating both.”

Investigators now suspect that when Tutankhamun died unexpectedly young, the lavish tomb he ordered for himself was not finished.

It could be that Ay seized the moment and ordered that Tut be buried in a smaller tomb.

With Tutankhamun gone and before any challengers could oppose him, Ay crowned himself Pharaoh and decreed that when he died, he would take Tutankhamun’s tomb.

Ms Ismail added: “Ay buried Tutankhamun in the smaller tomb, so he could have the bigger tomb for himself.

“This is the tomb that was intended for Tutankhamun, the tomb of Ay.”

The research and analysis suggests that Ay banished Tutankhamun to the smaller tomb in order to secure the great and lavish tomb for himself.

Later pharaohs essentially erased Tutankhamun from history, smearing his name as the son of a heretic.

But 100 years ago, when his tomb was discovered, Tutankhamun was reborn as a superstar, and has since gone on to become known as one of Ancient Egypt’s most revered leaders.