Archaeologists last week discovered a perfectly intact room in which slaves once lived in the ancient Roman city of Pompeii. Among the objects found were three wooden beds, a chamber pot and a wooden chest containing metal and fabric items. The discovery was made in Civita Guiliana, which lies around 700 metres north-west of Pompeii’s city walls.

Gabriel Zuchtriegel, director of the Pompeii archaeological park, said it is “certainly one of the most exciting discoveries of my life as an archaeologist”.

Archaeologists made the find almost a year after they found the remains of two victims of the AD79 eruption of Mount Vesuvius in the same villa.

Much closer to home, however, lies a “Bronze Age Pompeii”.

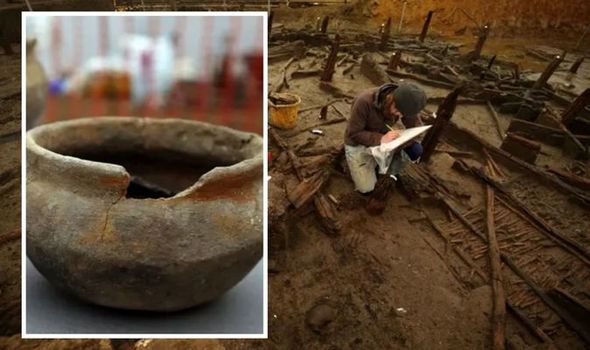

Almost 3,000 years after being destroyed in a fire, the remains of two large, wooden Bronze Age houses were discovered at a quarry site in Peterborough.

The houses, discovered in 2016, were remarkably well preserved.

Among the “unprecedented” collection, artefacts found inside included jewellery, daggers, spears, glass beads, huge food storage jars and drinking cups.

The Guardian reported a copper spindle found inside one of the houses still had thread wound around it.

A cooking pot in the house contained a wooden spoon and calcified food from the heat of the fire, suggesting the owners abandoned their house while cooking.

Both houses were built on stilts in a waterlogged fenland site, sitting right beside the former course of the river Nene.

Site director Mark Knight said at the time: “It almost feels rude to be intruding. It doesn’t feel like archaeology any more, it feels like somebody’s house has burned down and we’re going in and picking over their goods.”

During the fire, which ultimately destroyed the house, roof timbers collapsed onto the floor and sandwiched anything in between.

These then fell into the water, where the remains were sealed, for almost 3,000 years, by layers of silty mud and clay up to several metres deep.

Although it wasn’t entirely clear what caused the fire, Mr Knight speculated possible reasons could have been a cooking accident, enemy attack, or deliberate destruction and abandonment of the site.

The sheer number of artefacts found, whatever the cause of the fire, shows the inhabitants fled as quickly as they could.

The unprecedented discovery allowed Mr Knight and his team to investigate what the owners of the houses wore, the food they ate, right down to the chairs they sat on.

He said: “These people were rich, they wanted for absolutely nothing. The site is so rich in material goods, we have to look now at other Bronze Age sites where very little was found, and ask if they were once equally rich but have been stripped.”

The spine of a cow was found in the smaller of the two houses, suggesting a carcass was awaiting butchery.

A team of archaeologists from the University of Cambridge later discovered a skull near the presumed doorway of the larger house.

Historic England funded the project, which later unearthed a series of other remarkable things.

A large wooden wheel, the earliest of its kind, was discovered in 2016. A horse’s spine was also found nearby, suggesting it may have been part of a horse-drawn cart.

Further analysis of both human and dog coprolites at the site found the presence of fish tapeworms, giant kidney worms and others. It is the earliest evidence of human infection by such parasites in the UK.

Emerging evidence published by Cambridge University in 2019 suggests that the site was no more than one year old at the time it was destroyed by fire.

Unfortunately, around half of the settlement is thought to have been lost due to modern day quarrying.

The site lies around two kilometres (1.2 miles) south of the iconic Flag Fen, a Bronze Age site which is believed to have been a ritual landscape of the dead.

Archaeological work is ongoing at both sites.